Nick Dellow’s “Unissued on 78’s” CD: Jazz Delights from the Reject Pile

by Mark Gabrish Conlan • Copyright © 2021 by Mark Gabrish Conlan • All rights reserved

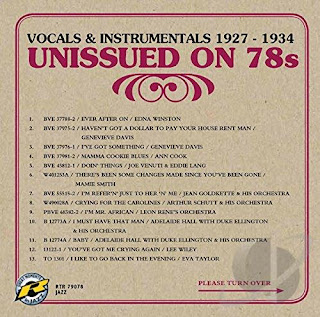

Recently I got in the mail from CD Universe (which has sent me so many e-mails promoting not only their music and movie releases but so many cannabis products I think any day now they’ll change their name to CBD Universe) an intriguing CD I’d ordered on the Retrieval Records label: Unissued on 78’s: 1927-1934. Producer Nick Dellow (who’s also a contributor to the Bixography Forum) began with a note in his liner booklet which said, “‘Unissued on 78’ means just that and no more. Certainly some of the recordings here have appeared on LP’s and even CD’s, but long enough ago for those issues to have become collectible in their own right.” I guess Nick put that in there to forestall people trying to nit-pick his selections to death and write him letters saying, “What do you mean, ‘unissued’? I’ve had some of these songs for years!” I did catch Dellow out on one odd mistake at the very beginning of his essay, when he wrote, “Before the Second World War, commercial recordings were invariably made using wax masters.” No, they weren’t; that was mostly true through the 1920’s but beginning in the 1930’s record companies started recording direct-to-disc masters on lacquer instead of wax. As I explained in my comments on The “American Epic” Sessions, the 2016 project for a PBS documentary that used reconstructed 1929 recording equipment to make records with modern artists, lacquer had four advantages over wax: it was more durable (wax masters were so fragile that, until they were processed and turned into metal parts, “you could ruin the wax with a toothpick,” record producer John Hammond recalled), it didn’t need to be kept warm before use (wax masters were warmed in a low-temperature oven and taken out only when they were about to be used; if they sat out too long the record developed a high-frequency whine about midway through that got louder as the record progressed), they didn’t need someone standing over the master with a brush to sweep away the excess wax; and, most importantly, they could be played back immediately so the producers and the artists could hear what they had just recorded instead of waiting for weeks until the metallurgists at the record company’s factory processed them. (For contemporary evidence that by 1937 lacquer instead of wax had become the standard material for recording, see the Paramount short Record Making with Duke Ellington, available on YouTube at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SJ0Vn7ul42s.)

There are 24 tracks on the Unissued on 78’s CD, and they run the gamut from classic blues (sung almost exclusively by women – in the 1920’s women blues singers were the superstars of Black entertainment and they sang to huge audiences in concert halls, vaudeville theatres and in tents; Bessie Smith started a tent show because no indoor venues big enough to accommodate all the people who wanted to hear her were open to Black performers and audiences) to out-and-out jazz to pop-jazz to an intriguing ensemble called Candy and Coco that were on the cusp between blues and jazz (more on them later). Some of the tracks here were songs that were not released at all when they were new; some are well-known recordings (like the dazzling “Doin’ Things” by violinist Joe Venuti and guitarist Eddie Lang) heard here in alternate takes; and at least two songs here push the envelope of “unissued on 78’s.” These are “Memphis Blues” and “My Old Flame,” recorded in 1934 by singer/actress/writer Mae West for her film Belle of the Nineties. Paramount, the studio that made Belle of the Nineties, put out those two songs, in which West was accompanied by the Duke Ellington Orchestra, as what were called transcription discs. They weren’t released to the general public but they were pressed and released to radio stations in hopes they would play them and promote the movie – and, since the records were taken from the same soundtracks used to make the film, their audio quality is considerably better than any of the other tracks that were recorded in the normal direct-to-wax or direct-to-lacquer fashion. Indeed, one of the mysteries of the history of the record business was why they clung so long to direct-to-disc recording technology even after higher-quality ways of recording sound had come into existence. Up until 1942, when Capitol Records licensed the soundtrack rights to the film The Jungle Book and dubbed their records of the film’s background score directly from the recordings made for the film, record companies refused to release film recordings. If they wanted to put out music from a film, they would have their own people re-record the songs in their own studios with their own equipment. The way these two Mae West recordings leap out in sound quality from the rest of this CD indicates how by 1934 movie studios were much better at recording than record companies. But, aside from a few experiments by Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra in the early 1930’s, record companies resolutely refused to use film equipment to make records, and it was only the advent of magnetic tape after World War II that led record companies to abandon direct-to-disc recordings and make their records on tapes, which were then dubbed to master discs for release as records.

The Unissued on 78’s CD begins with a performance by virtually unknown singer Edna Winston, doing a blues-ish pop song called “Ever After On” ostensibly written by W. C. Handy but drawing inspiration from the same folk source that produced the song “Hard, Ain’t It Hard.” Winston’s backup band includes Tom Morris on cornet, Bob Fuller on clarinet, and Charlie Irvis, a member of one of Duke Ellington’s band and (according to Ellington) the first of his musicians to use an unusual mute, and the overall selection is a quite appealing bit of jazz-based pop from the New York studios. The next three tracks are a different story: they were made in New Orleans In March 1927 as part of a “field recording” trip organized by Victor Records. At the time any bands outside America’s three largest cities – New York, Chicago, Los Angeles – was considered a “territory band,” in a lower tier of the music business. The only ways territory bands got to record were either to go to one of the three main cities (which often meant a laborious trek through the country, including attempts to set up gigs along the way so the band could make money and the trip could pay for itself) or to have the record companies come to them. At the time recording equipment was complicated, heavy, massive, delicate and difficult to move (once again, one wonders why they bothered when by the mid-1930’s film recording equipment was not only cheaper and better but also more portable; filmmakers of the 1930’s routinely shot sound out of doors, while record companies considered outdoor recording hopelessly impractical), so the companies would try to record as many artists as possible and stack up large numbers of master discs to make the trip worth their while. The most legendary and successful field recording trip was the one taken by Victor in August 1927, where they set up in a hotel in Bristol, Tennessee and sent out an appeal to anyone who could play what later became known as country music. They were there to record an established artist, Ernest Stoneman, who was tired of the rigmarole of having to go to New York or Chicago to record, but the trip paid off big-time when producer Ralph Peer discovered two artists who would become the first country superstars, the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers.

Victor’s trip to New Orleans earlier that year wasn’t either as artistically successful or as lucrative, but they managed to get one of the best New Orleans bands that hadn’t migrated to the bigger markets of L.A. or Chicago, cornetist Louis Dumaine and his Jazzola Eight. In addition to making four sides with the full band, Victor also recorded members of it backing pop-blues singers Genevieve Davis and Ann Cook. Dellow’s collection includes alternate takes of these titles (which were rare enough even from the original releases that Arnold Caplin’s Historical Records label released Cook’s “Mama’s Cookle Blues,” the same song she does here, on a late-1960’s compilation called Trumpet Blues), including Davis’s “Haven’t Got a Dollar to Pay Your House Rent Man” (which contains a verse also used in “Cold in Hand Blues,” memorably recorded by Bessie Smith and the young Louis Armstrong in New York in 1925) and “I’ve Got Something,” in which a male singer (Leonard Mitchell) suddenly pops up and turns the piece into a ribald duet that was probably what much of Black vaudeville sounded like. After the three pieces from New Orleans we get a sudden leap into a quite different style of jazz (Nick Dellow programmed the CD in strict chronological order, so we get quite a few such leaps): an alternate take of the classic “Doin’ Things” with violinist Joe Venuti and guitarist Eddie Lang. This is white jazz, not only because the musicians were Caucasian but because they’re playing in a light style with few of the blues inflections of the best Black players of the time (though Lang hung out with Black jazz-blues guitarist Lonnie Johnson and picked up some of the blues feeling from him).

The next song is “There’s Been Some Changes Made Since You’ve Been Gone” by Mamie Smith, who in 1920 had established Black music as a commercial genre for the record companies when her “Crazy Blues” became the first record by a Black artist to sell over a million copies. By 1928 Smith’s career was on the downgrade – more soulful singers like Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith had eclipsed her – so she decided to ramp up the raunchiness and make her songs more sexually explicit. This song – unreleased at the time, according to Dellow, because Columbia Records already had a version of the song by the husband-and-wife team Butterbeans and Susie (noted for their still astonishing record “I Want a Hot Dog for My Roll”) – is still amazing as she nonchalantly describes the parade of male visitors she’s had since she drove out the guy she’s addressing the song to and changed the locks behind him. (Later a blues singer named Bill Weldon would write the same situation from the man’s perspective, “Somebody’s Done Changed the Lock on Your Door.”) After that comes another wrenching change in style to Jean Goldkette and His Orchestra. Goldkette – who was born either in France or Greece, depending on what source you believe – became a major bandleader and booker in the Midwest and led a series of bands, including his flagship outfit whose home base was the Greystone Ballroom in Detroit, which Goldkette owned. Alas, his undercapitalized organization collapsed in 1927 and took his greatest band – the one from 1926-27 with Bix Beiderbecke, Frank Trumbauer, string bassist Steve Brown and arranger Bill Challis – down with it. In 1928 Goldkette assembled another band but aimed it at the market for dance music, which then meant light, frothy, tightly arranged syncopated pieces with bits of jazz spackled in. Goldkette is represented here by “I’m Refer’n’ Just to Her ’n’ Me,” with some good jazz playing (the notes on this CD name Sterling Bose as the trumpet soloist but put a question mark after his name, meaning it’s not certain he was on this record, though it sounds like him) and an O.K. vocal for the period by a man named Kay Palmer.

The next track is also by a white band, but a considerably better one, nominally led by pianist Arthur Schutt but also featuring the Dorsey Brothers – Tommy on trombone and Jimmy on clarinet and alto sax – both of whom would become major bandleaders in the swing era – and also featuring Leo McConville, a trumpeter who usually played the second part in studio bands led by more illustrious stars like Red Nichols. Unless the unknown second player on the instrument listed in Dellow’s notes is Nichols (at least an outside possibility), this gives us a rare opportunity to hear McConville in a solo role. Then we get a bizarre record called “I’m Mr. African” by Leon René, who would become a major songwriter with his brother Otis (they would start their own publishing company and collaborate on hits like “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South,” “When the Swallows Come Back to Capistrano” and “Boogie Woogie Santa Claus,” which made the Renés a lot of money even though it wasn’t a hit: it was one of those cases where the B-side of Patti Page’s record, “Tennessee Waltz,” was the one that got played and sold; the Renés also started their own record label and made some of the first recordings by Nat “King” Cole). The song is obviously a parody of the Tarzan character (MGM’s hit film Tarzan the Ape Man, which launched the series with Johnny Weissmuller in the title role, was released the same year as this record was made, 1932), with an unknown band except for a singer named “Banjo Buck” who’s obviously imitating Cab Calloway and may be Leon René himself.

From the ridiculous we go to the sublime: Adelaide Hall singing with Duke Ellington in two 1932 recordings of songs from Lew Leslie’s all-Black revue Blackbirds of 1928. Ellington’s manager, Irving Mills, grabbed the rights to publish the songs from the show, and it was one of the best deals he ever made: he got four songs that became huge hits and enduring standards, “I Can’t Give You Anything but Love,” “Diga Diga Doo,” “I Must Have That Man” and “Baby.” The show also launched the career of its leads, Bill “Bojangles” Robinson and Adelaide Hall, who got the star woman’s part when Florence Mills (for whom Ellington wrote the instrumental “Black Beauty”) suddenly died of appendicitis in 1927. Hall had already knocked on the door of stardom in an odd way: she was a dancer at the Cotton Club in New York City when Ellington rehearsed a new instrumental called “Creole Love Call.” Hall started singing along – not to Ellington’s melody but to a counterpoint line she made up on the spot – and Ellington heard it and said, “I like that. I want to put that on the record.” Hall did, and she was launched into an unexpected career as a singer; she’d originally recorded the songs from Blackbirds of 1928 with the pit band that accompanied the show, but in 1932 she remade “I Must Have That Man” and “Baby” with Ellington. Alternate takes from those performances are included here, and “I Must Have That Man” sounds overwrought, with too many of the “torch singer” affectations, including sobbing noises and sudden register drops. (Then again, I’m comparing her to the superb and more subtle versions recorded later by Billie Holiday in 1937 and Ella Fitzgerald in 1942, from which I learned the song.) “Baby” is something else again: the sinuous lines of the song (by white songwriters Jimmy McHugh and Dorothy Fields, who had worked at the Cotton Club and knew how to “write Black”) are done full justice by the Ellington band (especially the slithery clarinet obbligati by Barney Bigard) and Hall’s seamless switches from wordless “scat” singing to interpreting (and beautifully phrasing) the lyrics.

Hall appears twice more on the CD in a December 4, 1033 recording backed by Irving Mills’ in-house orchestra, the Mills Blue Rhythm Band. One of the songs, Sam Stept’s and Bud Green’s “Reaching for the Cotton Moon,” is one of those dreary oh-how-I-miss-the-South ditties that cluttered up the charts just then and were bad enough when white people sang them. With Blacks like Hall and the Blue Rhythm Band on board, they sound really ridiculous. Fortunately, the other song on the date, “Drop Me Off in Harlem,” is totally the opposite: based on an instrumental by Duke Ellington, the song’s added lyrics by Nick Kenny loudly and proudly proclaim the singer’s pride in Harlem and her utter rejection of all that down-home Southern crap. (It anticipates by eight years Jump for Joy, the musical Ellington presented in Los Angeles in 1941 in which he set out to explode every stereotyped depiction of African-Americans in entertainment in one go, with song titles like “Uncle Tom’s Cabin Is a Drive-In Now.”) Alas the four Adelaide Hall selections are broken by two other tracks, “I LIke to Go Back in the Evening” by singer Eva Taylor with her husband, Clarence Williams; and “You’ve Got Me Crying Again” by Lee Wiley with the Dorsey Brothers Orchestra. The Eva Taylor track is really retro, with Williams on jug and Floyd Casey on washboard; one wonders who the record company thought would be the market for this in 1933. (Maybe there wasn’t one: the master prefix is “TO,” which might mean it was a private record made for Mr. and Mrs. Williams rather than one intended for ordinary release.)

Nick Dellow’s liner notes describe Wiley as “swinging in a manner that bears comparison with Connie Boswell or Mildred Bailey at the same period,” but despite good backing by the Dorsey Brothers and a fabulous trumpet solo by Bunny Berigan, Wiley sounds uncomfortable here. Like Mildred Bailey, Wiley’s early records don’t offer more than hints of what she would become later (both singers really blossomed later in the 1930’s), and I suspect the song’s rank sentimentality put her off. The next year she shined on Johnny Green’s song “Easy Come, Easy Go,” a superb record that turned up on the two-LP set Eddie Condon’s World of Jazz in the 1970’s. (And any list of the great white women jazz singers of the late 1920’s and early 1930’s needs to include Annette Hanshaw along with Bailey, Boswell and Wiley.) The next two tracks are from one of Frank Trumbauer’s studio groups, recording for Brunswick in early 1934; Trumbauer had just returned to the Paul Whiteman band and these sides, “Break It Down” and “China Boy,” also turned up on the Mosaic Records boxed set of Bix Beiderbecke, Frank Trumbauer and Jack Teagarden from 1924 to 1936. They are nice, tight-knit band performances with the great Jack Teagarden on trombone and his brother Charlie Teagarden on trumpet, but there’s a mystery about the provenance of “China Boy.” Dellow’s discography describes it as a “special test made on portable equipment,” but Richard Sudhalter’s notes for the Mosaic box say only that it was a test pressing made for Trumbauer (it has the same telltale “TO” prefix on the master number that the Eva Taylor/Clarence Williams disc did). I really doubt that it was made on portable equipment since it’s heard on the Mosaic box right next to the originally issued take – and the sound quality on both versions is equivalent, which it wouldn’t have been if one had been recorded on a portable machine c. 1934.

After the two Trumbauer songs the sound quality perks up noticeably with the two Mae West tracks, recorded on film on a Paramount sound stage. In his autobiography Music Is My Mistress, Duke Ellington gave special shout-outs to Maurice Chevalier and Mae West for helping him break the color line and reach out to the white audience. Paramount brought Chevalier out from France in 1929 and he instantly became a star with his first film, Innocents of Paris. He had so much clout with the studio that when they offered him a live gig at the Paramount Theatre in New York, they said he could have any band he wanted to back him. Chevalier asked for Duke Ellington, and the “suits” at Paramount were shocked. “You can’t have a white singer in front of a colored band!” they told him. “Why not?” Chevalier replied. “In France we do it all the time!” By 1933 Paramount had weathered the Depression largely due to the smash successes of Mae West’s films She Done Him Wrong and I’m No Angel, and she served notice on them that she wanted to appear with Ellington’s band in her next film, Belle of the Nineties. The Paramount executives said they were fine with Ellington playing behind her on the recording stage, but of course they would have white performers synching to them on screen. “No,” said West, “I want Duke and his band in the movie.” At that time there weren’t many white singers who understood the blues as well as Mae West – her orgasmic moans that start her record of the Ralph Rainger-Leo Robin song “A Guy What Takes His Time” had probably never been heard from a white person on a record before – and she sang superbly with the Ellington band (though Ellington recorded another song from Belle of the Nineties, “Troubled Waters,” with his own singer, the marvelous and almost criminally underrated Ivie Anderson, and she fit the music even better). The vivid, luminous sound quality of these records made on movie film just adds to their appeal. Afterwards it’s back to ordinary direct-to-disc phonograph recording for the next track, “No Calling Card” by Joe “Wingy” Manone, a one-armed trumpeter from Texas who sang with a gravelly voice and was one of many (Bunny Berigan, Johnnie “Scat” Davis, Louis Prima) who seemed to be trying for “white Louis Armstrong” as their market niche.

The last four tracks on Unissued on 78’s were pretty astonishing: they come from a band called “Candy and Coco.” “Candy” was Candy Candido, who had a trick voice for comedy (he was in Bob Hope’s radio band for decades and not long after he made these records he appeared in the musical film Roberta with Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers) and “Coco” was a stunning guitar player named Leo Dunham. They made these four records in Los Angeles on September 19, 1934 along with a drummer, Monk Hazel (his first name is misspelled “Mark” in Dellow’s notes but is correct in the personnel list), and a pianist. The identity of the pianist is a real surprise: it’s Gene Austin, who was known almost exclusively as a singer – he was easily the most popular male pop singer of the 1920’s and his 1927 record of “My Blue Heaven” sold more copies of anything until Bing Crosby’s “White Christmas” in 1942. But he turns out to have been a quite good jazz pianist who not only plays stunningly on all four sides but composed two of them, “Kingfish Blues” and “New Orleans.” (The other two are jazz standards of the time, “China Boy” and “Bugle Call Rag.”) These records, without horns, have something of the same feel as the Venuti and Lang records made earlier or the Quintet of the Hot Club of France, with Django Reinhardt and Stéphane Grappelli which were to come. Dunham’s guitar sometimes sounds like a harp and sometimes like a trumpet, and these four records have a marvelously playful quality and a dazzling inventiveness that makes one wish more of this incredible music existed. (Apparently there are other records of them backing Austin as a singer, including “Dear Old Southland” and “After You’ve Gone.”) Overall, the Unissued on 78’s compilation is a joy – maybe you get whipsawed a bit too much between jazz styles, but about the only song here that makes you go, “Well, I can hear why they didn’t release that!” is Leon René’s “I’m the African.” Aside from that, there isn’t really a clunker in the bunch, and Nick Dellow and his colleagues at Retrieval Records deserve credit for putting out this fascinating collection of rarities.

Comments

Post a Comment